Areopagus Volume LXXX

Areopagus Volume LXXXWelcome one and all to the eightieth volume of the Areopagus. No poetry to sing us in this week, neither any timely musing nor comment on the weather — the Areopagus begins at once! I - Classical MusicZadok the Priest & the Champions League Anthem George-Frederick Handel (1727) & Tony Britten (1992)

Imagine you have just been asked to write an "anthem" for the world's most prestigious club football competition, one with a long and storied history, watched by millions of people around the world, and worth a fortune economically. What would you do? This was precisely the job given to Tony Britten, an English composer, in 1992. The European Cup, founded in 1955 and contested by the best football clubs in Europe, was being reorganised into the "Champions League". As part of this rebrand UEFA (the governing institution for European football) commissioned a piece of music for which the players would line up before the match, as happens with national anthems in international football. So Tony Britten turned to George-Frederick Handel, the eternally popular German composer who dominated English music in the 18th century. Specifically, Britten chose to adapt Zadok the Priest, which Handel had composed for the coronation of King George II in 1727. This was named after Zadok, one of the high priests of Jerusalem who crowned the Biblical king David, and embodies with its soaring strings and heavenly chorus the elegance of Baroque music. A bold choice by Britten, but one that did everything it was supposed to and more: the delicate grandeur of Handel's anthem, transmuted by Britten, has lent the Champions League an aura of sophistication and an unparalleled sense of occasion. Star players have often said that, as children, they dreamt of lining up to hearing the anthem play — and I must confess that, as a child, my cousins and I would listen to it before playing football in the back garden. Britten's adaptation is a well-known story, but I don't think he gets enough credit for how successfully he reworked Zadok the Priest. The inspiration is clear, but this is far from a straightforward remixing of Handel's work. I have included both pieces, Handel first and Britten second, so you can get a sense of the transformation. I suppose this story also illustrates that "old music" (as some might be tempted to call it!) has timeless relevance. Just as Handel's Baroque strings uplifted the hearts of Georgian Britain, so Tony Britten's adapted version has captured the imagination of people from all around our 21st century world. Much has changed, politically and technologically and otherwise, but it seems that music has an almost unique power to rise above such context. II - Historical FigureMatthew Arnold An Elegant Jeremiah? Matthew Arnold was born in 1822. His father was Thomas Arnold, who as headmaster of Rugby School led a revolution in Britain's public school system and became a prominent figure in the Victorian cultural scene. Thus great expectations lay upon young Matthew — and he readily took on the mantle, inheriting his father's restless sense of public duty. But the best way to describe Arnold's life, I think, is as one of duality. This is true in two ways. First, regarding his career, Arnold worked both as a Professor of Poetry at Oxford University and as an Inspector of Schools for the government. He was simultaneously an academic in his ivory tower, giving esoteric lectures or writing sensitive poetry, and a tireless, overworked reformer dedicated to improving the quality of education. We take national, standardised education for granted, but once upon a time it was little more than a daydream. It is in part thanks to the work of Matthew Arnold that this changed. As he was wont to say:

Porro unum est necessarium — one thing is needful; organize your secondary education. But it was as a poet that Arnold first made a name for himself, and because of which he was appointed to his role at Oxford. What was Arnold's poetry like? Emotional, contemplative, even mysterious. From The Future: A wanderer is man from his birth. He was born in a ship On the breast of the river of Time; Brimming with wonder and joy He spreads out his arms to the light, Rivets his gaze on the banks of the stream. His reputation was mixed; people regarded him as good, but perhaps not quite great. This is made clear by an entry in the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica which discusses Arnold's place in the pantheon of the best Victorian poets: On the whole, his place in the group will be below all the others. But in the 1860s Arnold turned his back on poetry and poured his energy into writing about the state of society. His prose style, unlike his poetry, was clear, tongue-in-cheek, and admirably self-aware. This touches on another of the dualities that seem to define Matthew Arnold: the conflict between his public image and the man himself. That same article from the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica explains this rather colourfully — and also reveals how differently encyclopaedias were once written! His prose was so self-conscious that what people expected to find in the writer was the Arnold as he was conceived by certain “young lions” of journalism whom he satirized—a somewhat over-cultured

petit-maítre—almost, indeed, a coxcomb of letters. On the other hand, those who had been captured by his poetry expected to find a man whose sensitive organism responded nervously to every uttered word as an aeolian harp answers to the faintest breeze. What they found was a broad-shouldered, manly—almost burly—Englishman with a fine countenance, bronzed by the open air of England, wrinkled apparently by the sun, wind-worn as an English skipper’s, open and frank as a fox-hunting squire’s—and yet a countenance whose finely chiselled features were as high-bred and as commanding as Wellington’s or Sir Charles Napier’s. The voice they heard was deep-toned, fearless, rich and frank, and yet modulated to express every nuance of thought, every movement of emotion and humour.

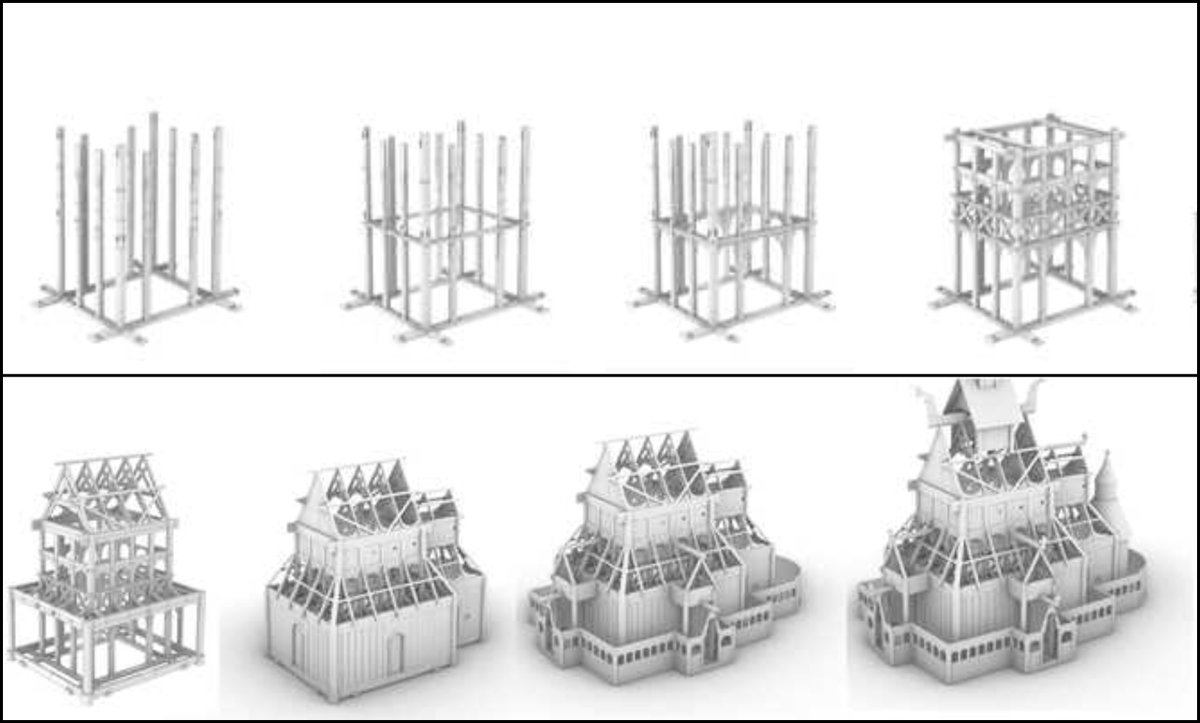

Arnold's critical watershed was a series of six articles written for Cornhill Magazine and published in 1869 as a single volume called Culture and Anarchy. In it Arnold fought against the idea that "culture" was a delicate and fanciful thing to be done in one's spare moments, a mere past-time for people with money to spend and an image to uphold. Rather, Arnold believed culture was needed to solve the urgent problems of his modern day, because it was a unifying and uplifting force that rose above mere politics or economics: The whole scope of the essay is to recommend culture as the great help out of our present difficulties; culture being a pursuit of our total perfection by means of getting to know, on all the matters which most concern us, the best which has been thought and said in the world, and, through this knowledge, turning a stream of fresh and free thought upon our stock notions and habits, which we now follow staunchly but mechanically, vainly imagining that there is a virtue in following them staunchly which makes up for the mischief of following them mechanically. Among a sea of fascinating observations he remarks on the danger of reading nothing but newspapers: More and more he who examines himself will find the difference it makes to him, at the end of any given day... whether or no, having read something, he has read the newspapers only. And freely admits that society was changing like never before: But now the iron force of adhesion to the old routine,—social, political, religious,—has wonderfully yielded. These are both examples of "old-new" problems, are they not? People reading nothing but news (or, in our case, the fruits of social media) and rapid social change. It was in this familiar environment that Arnold defended culture against the accusation that it was, at best, nothing but curiosity and learning for learning's sake. He believed it was a force for moral good in the world: Culture is then properly described not as having its origin in curiosity, but as having its origin in the love of perfection; it is a study of perfection. It moves by the force, not merely or primarily of the scientific passion for pure knowledge, but also of the moral and social passion for doing good. How did people respond? Noisily! One reviewer called him "an elegant Jeremiah", in reference to the doomsaying Biblical prophet, and others satirised his light-hearted style. But Arnold did shift public debate and helped frame, especially with the terms he introduced, the ongoing cultural discussion in Victorian Britain. For example, Arnold's most concrete legacy is probably our continued use of the word Philistine, which Arnold introduced into the English lexicon, albeit more pejoratively and less subtly than he would have liked. Arnold's influence, or at least his presence in public discourse, is made clear by how many times he was caricatured. One must be a prominent figure to be invoked, for good or bad, so often. The 1911 article (written, admittedly, at a time when Victorianism was going fast out of fashion) has this to say about Arnold's work as a critic: Perhaps, indeed, the place Arnold held and still holds as a critic is due more to his exquisite felicity in expressing his views than to the penetration of his criticism. Well, whatever people did or did not say, Arnold pursued his calling with vigour until his sudden death in 1888 by the inherited heart condition that had also claimed his father's life. Some writers shine brightly for a while but, as times change, subside. Much of Arnold's writing falls into this category, especially concerning the complex inter-denominational religious politics of 19th century Britain. But Arnold's belief in culture as a unifying force is perhaps more relevant than ever. He was concerned that Victorian society had become — amid a churn of unprecedented global changed — provincialised. By this he meant it was splintering into factions who wanted nothing more than to overcome their opponents. In our fractured age of social media this is a challenge with which we are all too familiar. Culture and Anarchy is a strange treatise, but one that demands to be read again over a century and a half after it was first written. How to conclude? With the opening stanza of Matthew Arnold's most famous and enduringly popular poem, Dover Beach. Make of it what you will — he would certainly have you do so! The sea is calm tonight. The tide is full, the moon lies fair Upon the straits; on the French coast the light Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand, Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay. Come to the window, sweet is the night-air! Only, from the long line of spray Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land, Listen! you hear the grating roar Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling, At their return, up the high strand, Begin, and cease, and then again begin, With tremulous cadence slow, and bring The eternal note of sadness in. III - SculptureMoche Portrait Jars In northern Peru, between the 1st and 8th centuries AD, there flourished a civilisation whose greatest city was near the present today Peruvian town of Moche — thus they are called the "Moche culture" or "Moche civilisation". This was not one big empire or country so much as a network of cities, regions, and peoples with broad cultural similarities and political links. They remain, compared to other ancient civilisations, somewhat mysterious. But thousands of artefacts have survived, including a great deal of incredibly advanced, wonderfully unusual pottery. Among the many different kinds of pottery produced by the Moche there is one, generally called "portrait jars", that stands out. These portrait jars are startlingly lifelike. Most Pre-Columbian art — and, indeed, the vast majority of ancient art around the world — was exaggerated, expressive, and symbolic. The Moche are an exception to this rule perhaps exceeded only by the statuary of Greece and Rome. But, more than being lifelike, Moche portrait jars are also incredibly idiosyncratic. Some of these faces are missing an eye, or have a cleft-lip, or seem to have some degree of facial paralysis. Others are laughing, ogling, smiling, glaring, and possibly even sneezing. Such unidealised realism has always been rare in art, and one wonders why the Moche ended up creating them. It also speaks to their technical mastery of the craft, of course. These portrait jars are a clue to what life was like in the Moche civilisation, and what the Moche people were like, and how they thought about their world. But deducing what they were used for and what they really mean is hard work, and scholars have been working tirelessly for decades to piece together their lost world. For me, at least, I think there must be some significance in how lifelike and frequently unflattering these portrait jars are. There is something almost humorous, even gently ironic about them. Rather than copying inherited models, it seems individual potters had the freedom to pursue their own inclinations or least create new designs inspired by people around them. Thus it was, we may conclude, a living school of art. And the consequence is that one thousand years later, long after the Moche have disappeared, these portrait jars allow us to almost literally look them in face and ask, "who were you?" Such is the power of art. IV - ArchitectureBorgund Stave Church Is this church real? That is the first question many people have when they first see Borgund Stave Church in Norway. Well, though it looks like something from a fantasy film, this is a real building — one made entirely from wood and approaching 900 years old, no less. Shortly after Norway officially adopted Christianity in the 11th century there began a boom in church construction, often on sites once used for pagan worship, that lasted for three hundred years. During this phase an entirely unique form of building emerged: the wooden stave church. More than 1,000 were built in Norway alone, with others in Denmark, Sweden, and Britain. Plenty of stone churches were also built, but it was far more common in Medieval Norway to make them with wood, more so than anywhere else in northern Europe. Thus, of the world's thirty surviving stave churches, twenty eight of them are in Norway! But what is a stave church? The name comes from how they were built — with staves, which are vertical posts used to create a box-shaped structural core around and upon which aisles or gables could be added. Wall timbers were fitted into this frame, often vertically, which marks them out from other wooden buildings where the walls are made with horizontal planks. And so, though plenty of Medieval buildings were wooden, the unusual design features of stave churches make them unique.

But the construction of these stave churches stopped in the 14th century, largely because of social and religious upheavals. When church construction resumed the old stave model was not adopted. Thus their numbers have declined dramatically, primarily because wood is vulnerable to fire. But that is not all — we cannot forget that people in the past were far less cautious with old buildings than we are. So, though many Medieval stave churches did burn down, plenty were "refurbished", demolished, or simply left to rot. Torpo Stave Church, built in 1192, was narrowly saved from "modernisation" in 1875; a new stone church was built instead. The one surviving stave church outside Scandinavia, in Poland, was moved there in 1842 thanks to the painter Johan Christian Dahl, who purchased it in order to save it from demolition and convinced his friend the Crown Prince Frederick William of Prussia to pay for its reconstruction elsewhere. The most immediately striking feature of Borgund Stave Church — along with being made of wood, of course — is how its gables are piled atop one another. These cascades of steep rooflines and slender turrets are fantastical and look like something straight from a novel. This striking impression, at once charmingly ramshackle and darkly mysterious, is enhanced by the "dragons" at the end of the rooflines — a motif which surely has roots in Norse mythology. The roofs and walls of stave churches are usually covered with wooden shingles. This is what gives them the impression of having scales — almost dragonlike, you might say! Borgund is a special case in this regard, for whereas most stave churches are orange or pale brown, Borgund is an incredibly dark shade of brown, verging on black, because of the protective tar that has been applied to it down the centuries. Another unusual feature of an already strange building. The setting of stave churches is also a major part of their aesthetic character. These churches — wondrous enough in any case — are elevated by the mountains, forests, and lakes of the Norwegian landscape, often clad in mist or snow. Their interiors are equally captivating. First, because they are entirely wooden, which is a strange sight given that most buildings are made of stone or brick, and often have plastered or painted walls anyway. Second, because the interiors of many stave churches tend to be both very tall and very narrow. For example, this is the view you get when looking up inside the church at Borgund.

Stave churches are also decorated with a kind of art unique to Scandinavia and parts of the British Isles. This is neither Romanesque nor Gothic — these swirling, interlocking patterns have their genesis in Viking art. The most famous carvings are at Urnes Stave Church, built in about 1130 (left) though Borgund also was decorated with some of these delightful patterns (right). Other elements of stave church design do show influence from foreign schools of architecture, Romanesque in particular, but art like this is thoroughly Norse in character. Altogether, then, the stave churches of Norway are a genuinely unique subgenre of architecture. Partly because they are wooden buildings made during the Middle Ages which have managed to survive, partly because of their curious Norse-Christian heritage, and partly because of their unusual construction methods. And, of course, their fabulously magical design simply looks like nothing else. The era of stave churches may have been only a short chapter in the history of world architecture, but it was one that produced wonders. And the finest of them, or at least the most striking, is at Borgund — a fantastical church that cannot fail to kindle the imagination. V - RhetoricHyperbole Hyperbole is a rare example of an ancient rhetorical term that is fully entrenched in modern language. Though we use devices like chiasmus, apophasis, and antanagoge all the time, the terms themselves are not widely known. Hyperbole is different. Why? Perhaps because it is easy to explain and thus finds itself invoked as an example of "a literary device" when students are asked to analyse poetry in school. The other reason is that it is probably the most common rhetorical device of all. Hyperbole is a form of exaggeration, sometimes but not always combined with a metaphor. When we say, "I've got a million missed calls," that is an obvious case of hyperbole. We do not literally have one million missed calls, and we do not claim to; rather, by using such an inflated figure, we impart to our listener that there are an awful lot of them. Still, one wonders whether saying the real number, if it really is so high, might have been more effective. But that is humanity — we are drawn inexorably toward enlarging the truth. Every headline and every analyst tells us that so-and-so is "the worst thing ever" or some new development "will change history" and such like. Those who abuse hyperbole end up like the boy who cried wolf. Language becomes deadened and we simply pay less attention to what is being said; thus the hyperboles are ratcheted up and, thanks to the law of diminishing returns, are soon replaced by even more bombastic, doom-foretelling spoof. I say all this by way of introduction to something that Aristotle said two and half thousand years ago in his treatise On Rhetoric; it comes to mind every time I read the news:

Hyperboles are for young men to use; they show vehemence of character; and this is why angry people use them more than other people. VI - WritingHumble Beginnings So you want to write something. But what shall it be? It is very easy to get carried away and start with a project that is big, bold, and complicated. Ambition can be a force for good — but it can also hamper our ability to learn and improve. It was because of this that, for centuries, it was standard practice in the world of poetry to begin with something simple. That it is to say, rather than attempting immediately to write an epic, poets would first write something shorter and on a smaller scale, with a reduced cast of characters and a handful of clear, well-established themes. And most of the time the setting for this initial foray was pastoral. The best example is Virgil, famous now for having written the Aeneid, which was something like the national epic of the Romans. It described the journey of Aeneas and his compatriots who, fleeing from Troy, endured years of travail and tragedy before settling in Italy. But before Virgil turned to the epic genre he had written the Eclogues, a set of ten miniature dramas featuring shepherds, and the Georgics, which is essentially a four-part description and explanation of agriculture. Before Torquato Tasso composed his epic Jerusalem Delivered he wrote a romantic pastoral play called Aminta. And John Milton, years before his Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained, wrote the much shorter L'Allegro and Il Penseroso, in both cases contemplative poems inspired by the classical model. Edmund Spenser, regarded in his lifetime as "the prince of poets", did much the same. His first published work was the Shepheardes Calendar, a sort of review of the twelve months of the year in the form of a dialogue between various rustic characters, written in an archaic style to make it feel more Medieval. The Shepheardes Calendar is wonderful in its own right — but one can also feel Spenser experimenting with and beginning to master the techniques and ideas that he brought to full fruition in the much longer, far more ambitious Faerie Queene. So we mustn't think of these pastoral preludes as simple or paint-by-numbers. The point was that, by limiting the scope of a writer's subject matter, they were forced to make the most of it. Thus many of these shorter works are bona fide masterpieces. Orson Welles once said that an absence of limitations is the mortal enemy of creativity — and he was correct. How often do we see talented people who fail because they have been too ambitious? So there is a lesson here, not only for writers but for film-makers, musicians, painters, and would-be artists of every kind. How to begin? Set yourself limits and scale back your ambitions. Rather than failing to do something grand and achieving nothing thereby, better to hone your skills by perfecting something simple. VII - The Seventh PlinthThe Reader's Calendar Last week I asked you about your favourite month. The responses were so plentiful and lovingly written that I have no choice but to hand this seventh plinth over to you, my readers, and your wonderful answers: Paris C My favorite month is October. It is not a month that belongs to my favorite season, which I think is a funny little contradiction that proves the nature of myself as a human (and of all of us, to some extent). October is precious to me because of its timing in my life, as well as its contradictory nature; it remains scorching hot in October where I live despite it being revered as an autumn month, and I celebrate my half-birthdays every October more ardently than I celebrate my actual birthday in April (with the exception of this year, a contradiction in itself). October is a funny little month—long, looming, and lovely—and then as quickly as it comes, it is gone, and now we are kicking off the winter months. A transitional month, of sorts, but one that feels like it has created its own place, time, and mood in my heart of hearts. Mohammad M Ramadan. Fast and see :) Phil V September is my favourite month. I am a British man who is now also an Australian man and as such my seasons have flipped a full 180 degrees on me.

September used to be the month of shortening nights, cold damp weather, but with the distant glow of Christmas in the distance. It is now the opposite. It's not eh survival through (the mild) Sydney winter and the oncoming of the summer with the various fire risks that come with it.

It is a perfect metaphor for how my life has changed over the last ten years.

Keith K My favourite month is July. First of all it's summer. More importantly l married my beautiful wife Ali on the 12th July and we had our wonderful son Tom on 1st July. It is also the cricket season. The garden is in fine shape with plenty of colour and the days are still long. It's basically the month to celebrate being alive. VR Like with many "my favourite" questions, I'd argue that a truly perceptive mind has no favourite month: they all have their external merits, plus they vary significantly based on geographical location.

One could assume that socio-cultural and economic activities subjectively imbue certain times of the year with more "happiness", such as Christmas time in Western societies or Eid in the Muslim world when families get together, or Summer in the Northern Hemisphere since that's when many families have holidays.

But at the essence, "what's your favourite" questions always beg answers that are too limited in terms of perception.

Jane L It has to be May ‘The flowers appear on the earth, the time of the singing of birds is come,’ and the voice, in England anyway, of the blackbird is heard throughout the land. The blackthorn still blooms and hawthorns froth in both town and countryside. I love its scent although many don’t and the children call it Motherdie as it should not be brought into the house. In the fields the shining yellow of meadow buttercups is transmittable on the chins of children. It’s the month when the swifts arrive from their winter stay in Africa and lilac blooms in countless suburban gardens. And above all it’s when the woods are carpeted with bluebells, stitchwort and wild garlic. Surely one of the best beautiful sights in all the land. Sally J June because the days are long and often warm, summer fruit is ripe to eat and somehow everything seems possible. Frannie G May in Sydney (Australia) is my favourite month. The days are warm, the nights are cool, and the weather calm, after the wildness of April.I begin choosing books for the long winter nights. And think about soups, casseroles and red wine Meg F I would have to say September. (Not just because it's my birth month, I promise.) There is a Lucy Maud Montgomery sonnet– entitled "September"– that I simply love.

Lo! a ripe sheaf of many golden days

Gleaned by the year in autumn’s harvest ways,

With here and there, blood-tinted as an ember,

Some crimson poppy of a late delight

Atoning in its splendor for the flight

Of summer blooms and joys

This is September.

I think Maud sums up exactly how I feel about the month. September is a bridge between summer and autumn– it's nostalgic and ephemeral and unites old with new. Where I live the weather is delightful for practically all thirty days, although it depends as to whether or not one needs a coat; some years sweaters and scarves and hats come out of their hibernation and others the heat of summer lingers. As an academic and student, it is the month of getting into the rhythm with studies again, and the perfect time to make habits and plans for the coming months. September includes copious amounts of tea, lots of walking, reading, writing– and watching. What a joy it is to observe the turning leaves fall to the ground and the migratory birds overhead. For me, September is the start of the great metaphor of habitual death, and truly the start of the waiting period until the great Resurrection.

Kari M I do not have a favorite month. Each one has its days of pure joy or deep sadness. I can appreciate the dark and cold days of January when I can cozy up and read all day as much as a warm and sunny day in May when I am out in sunshine and fresh air planting my garden. The crisp autumn days bring joy as do sultry summer months when I need to sit in the shade and watch bugs twitter and ice melt. Jill M April comes like an idiot, babbling and strewing flowers.—Edna St. Vincent Millay

My favorite month is April. That’s when the wisteria bloomed at my former home. There is something about the ephemeral blossoms of April that reflect my observations about the cycle of existence: Birth. Life. Death. It is simple Beauty in the universe, no matter the time span I consider. It also happens to be my birthday month, so there’s that too. More prosaic perhaps, but nonetheless enjoyable for me. Carol D My favourite month is April in the southern hemisphere and October in the northern. Mid autumn seems like a pause in the Earth’s movement round the Sun; there’s a certain calmness with mild days, slightly chilly nights and leaves turning but not yet dropping. It’s a time when Yin and Yang are in perfect balance: bright Yang autumn colours by day and cool Yin temperatures by night. I’m writing this on a mild late April morning in Sydney, gazing at a bright claret ash in my garden while taking my time over a coffee and leisurely reading this week’s volume. Perfection. Ronald S Simple question with very simple answers. Yes not just one.

It all depends on the criteria used for giving the month its right value and appreciation.

Is it a birth date? Then everyone knows the answer

Is it related to specific remarkable events or memories? Then this is well determined to each

Is it related to weather? Then to each her/his own appreciation of the weatherly mood, its colours, or even its timely activity (sport?)

But to keep it simple and based on just the above, all and none

Tom W September for me. The ground seems to have a residual warmth, boughs hang heavy with leaves or fruit and wildlife is at its most active (because best-fed) time of year. The days are drawing in but summer culminates in a final blast, with the very beginnings of autumn crowing it in gold. The perfect month in which to sit outside of an afternoon with one’s beverage of choice and watch the time go by. Sam A My favourite month is July. With the end of June marking the end of the first part of the year, July marks the beginning of the second half of the year. For me, it's like a reset, like checking your half way score and getting ready for the second round of the exam that is life.In July, one takes stock of the achievements of the year and then makes arrangements, adjustments for tackling what comes next.

It's like part 2 after finishing part 1.

Natalie E My favorite month is whichever brings the loveliest weather and temperatures, usually May or June, but sometimes fall months come with nice, warm rain and thunderstorms that I love. But this question also leads me to wonder why we, as a society, are so focused on favorites. "What's your favorite color?" – perhaps the most commonly asked question to a child. I propose that we seek to appreciate the beauty in all of the colors... and in all of the months. Kevin T The turning of the page. The passing of the day, the week, the month, the season, the year. And you ask me to choose. Some seasons are full of sorrow and heartache, others of joy and celebration. Do I choose I the bleak beautiful cold of winter? The sweltering heat of summer? April showers or October’s showy colors as leaves put on their own funeral procession? I refuse to choose. I aspire to celebrate today, and choose to be grateful for what it may bring - and, perhaps on a good day, to view it with a bit of wonder and hope. Question of the WeekFor this week's question to test your critical thinking I ask: What is the ultimate purpose of education? Email me your answers and I'll share them in next week's newsletter. And that's allThe verse of Matthew Arnold is echoing in my head — strange, how words when arranged in a certain way stay with us and float invisibly in the corner-shadows of our minds. So I offer you, by way of postlude, the last stanza of Dover Beach. Ah, love, let us be true To one another! for the world, which seems To lie before us like a land of dreams, So various, so beautiful, so new, Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light, Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain; And we are here as on a darkling plain Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, Where ignorant armies clash by night. Like all Arnold's work it prompted praise and mockery in equal measure. If it does mean something to you, so much the better; if not, tant pis. Cheerio! Yours, The Cultural Tutor

|

The Cultural Tutor

A beautiful education.

Areopagus Volume XC Welcome one and all to the ninetieth volume of the Areopagus. No wordish prelude this week; let us get on with the show! Another seven short lessons, altogether promptly, begins... I - Classical Music Plaisir d'Amour Jean-Paul-Égide Martini (1784) Performed by Isabelle Poulenard & Jean-François Lombard;Harp: Sandrien Chatron; Violin: Stéphanie Paulet; Flute: Amélie MichelThe Feast of Love by Jean-Antoine Watteau (1719) Jean-Paul-Égide Martini (a fabulous Francisation of...

Areopagus Volume LXXXIX Welcome one and all to the eighty ninth volume of the Areopagus — and we're back! It has been two months since you last heard from me, an unplanned interlude that was the result of one happenstance after another. No longer. From now on you can expect the Areopagus on a far more regular basis. There is much I might tell you about, plenty of exciting news, but for now there is only one update I should share: soon I will be moving the Areopagus to Substack, a different...

Areopagus Volume LXXXVIII Welcome one and all to the eighty eighth volume of the Areopagus. First: more and thrilling (a little bit of hendiadys for you) news from my patrons at Write of Passage — enrolment for their next cohort opens tomorrow! A cohort for what?! For learning how to write. It's a course that places you in the heart of a writing community and teaches, specifically, the art of writing online. This is the Internet Age, after all, and Write of Passage have placed themselves at...